No Pensions for Ex-Slaves

How Federal Agencies Suppressed Movement To Aid Freedpeople

By Miranda Booker Perry

United Nations, New York, 18 February, 2011 - With 80 per cent of the world's people lacking adequate social protection and global inequalities growing, top United Nations officials are calling for a new era of social justice that offers basic services, decently paid jobs, and safeguards for the poor, vulnerable and marginalized. " Social justice is more than an ethical imperative; it is a foundation for national stability and global prosperity," Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said in a message ahead of the World Day of Social Justice, observed on 20 February. " Equal opportunity, solidarity and respect for human rights, these are essential to unlocking the full productive potential of nations and peoples." Full story: http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=37566&Cr=social+protection&Cr1 =

U.S. courts and legislatures have become the premier venues for reparations claims of various sorts, and many American political leaders have been outspoken in demanding that leaders of other nations (particularly the current government of Japan)acknowledge and make amends for the misdeeds of their predecessors.

Disc 1 Of An Excellent Lecture By Dr. Yaffa Bey. Enjoy! Ma'at Hotep.

On the other hand, many Americans remain distinctly uneasy about broaching aspects of their own history, particularly in regard to slavery. While recent years have seen a proliferation of national and institutional apologies for various offenses, a proposed

apology for slavery – a one-sentence Congressional resolution introduced in 1997 apologizing to “African Americans whose ancestors suffered as slaves under the Constitution and the laws of the United States until 1865” – died before it could even come up for discussion on the floor of the House of Representatives. It is difficult to say

precisely where this reticence about slavery comes from, but it seems to us to be a matter worthy of further reflection

Dear lorenzo,

Have you seen the news out of Wisconsin, Ohio and now Indiana?

Working men and women, tired of Republicans attacking their ability to make a living instead of promoting the jobs plan they’ve yet to develop, have taken to the streets to fight for their rights in the workplace.

Here in Indiana, Republicans in the General Assembly are preparing the same attacks on Hoosier workers.

In the past week, these out-of-touch lawmakers have attacked collective bargaining, the right to freely associate in unions, job security and jobs themselves. These bills do nothing to create a positive future for Indiana or put us back on the right economic track. It’s just more of the same political gamesmanship we’ve come to expect when Republicans are in charge of everything.

But now is the time to have our voices heard! Over the next three days, Hoosiers will be marching on the Capitol in Indianapolis. Will you join us as we show our support for hard-working families who deserve to be treated fairly?

The Union victory in the Civil War helped pave the way for the 13th amendment to formally abolish the practice of slavery in the United States. But following their emancipation, most former slaves had no financial resources, property, residence, or education—the keys to their economic independence.The Cherokee Freedmen Controversy is an ongoing political and tribal dispute between the administration of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen related to their tribal membership. After the American Civil War, slaves held by Cherokee were freed, and the Cherokee Freedmen were made citizens of the tribe in accordance with an act of the Cherokee National Council in 1863. A treaty made with the United States government in 1866 further cemented the freedmen's place as Cherokee citizens, giving them and their descendants federally protected rights to citizenship. The Freedmen were Cherokee Nation citizens until the early 1980s. The Cherokee Nation stripped them of voting rights and citizenship, a situation that lasted for more than two decades.

Efforts to help them achieve some semblance of economic freedom, such as with "40 acres and a mule," were stymied. Without federal land compensation—or any compensation—many ex-slaves were forced into sharecropping, tenancy farming, convict-leasing, or some form of menial labor arrangements aimed at keeping them economically subservient and tied to land owned by former slaveholders.

This is awesome!

youth on the move w world history w/Africans of the Diaspora Included in education of world history

"The poverty which afflicted them for a generation after Emancipation held them down to the lowest order of society, nominally free but economically enslaved," wrote Carter G. Woodson in The Mis-Education of the Negro in the 1930s.

In the late 19th century, the idea of pursuing pensions for ex-slaves—similar to pensions for Union veterans—took hold. If disabled elderly veterans were compensated for their years of service during the Civil War, why shouldn't former slaves who had served the country in the process of nation building be compensated for their years of forced, unpaid labor?

By 1899, "about 21 percent of the black population nationally had been born into slavery," according to historian Mary Frances Berry. Had the government distributed pensions to former slaves and their caretakers near the turn of the century, there would have been a relatively modest number of people to compensate.In March 2006, the Cherokee Nation's Supreme Court ruled that the descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen were unjustly kept for over 20 years from enrolling as citizens. They were allowed to register and to become enrolled citizens of the Cherokee Nation. Principal Chief Chad "Corntassel" Smith called for an emergency election to amend the constitution. A petition for a vote to remove the Freedmen descendants was circulated and Chief Smith held an emergency election. [1] As a result of the amendment's approval in a referendum, the Freedmen descendants were removed from the Cherokee Nation tribal rolls. They have continued to press for their treaty rights and recognition as tribal members

But the movement to grant pensions to ex-slaves faced strong opposition, and the strongest came not from southerners in Congress but from three executive branch agencies. It was opposition impossible to overcome. William Wells Brown. Born 1814 in Lexington, Kentucky, slave of his father, George Higgins. Brown escaped in 1834 and became a conductor on the Underground Railroad and a featured speaker for the American Anti-Slavery Society. He wrote several books before his death in 1884. Brown, My Southern Home, p. 202. Henry Clay Bruce. Born 1836, slave of Lemuel Bruce. Sold at the age of eight to Jack Perkinson of Keytesville, Missouri. Hired out to different people, and returned with Perkinson to Virginia in 1847. After the war, he and his wife moved to Leavenworth, Kansas. He died in 1902. Bruce, The New Man, pp. 12, 36-39, 105-6, 111. Julia Bunch (GA). Slave of Jackie Dorn of Edgefield County, Georgia; given as "a wedding gift." Belle Buntin (AR). Born in Oakland, Mississippi, slave of Johnson and Sue Buntin. "They had two children: Bob and Fannie. He had a big plantation and four families of slaves." Jeff Burgess (AR). Born ca. 1864 in Cranville, Texas, slave of Strathers and Polly Burgess. Will Burks Sr. (AR). Born ca. 1862 near Columbia, Tennessee. Son of Bill Burks and Katherine Hill; brother to four boys and three girls; slave of Frank and Polly Burks. Mahala Burns (AL). Slave from Hammond, Alabama. Annie Burton. Born ca. 1858 near Clayton, Alabama, and raised by her mistress. She moved to Boston in 1879, then to Georgia and Florida, where she ran a restaurant before circling back to Boston. Burton, Memories, pp. 35-36. Vinnie Busby (MS). Born ca. 1854, slave of J. D. Easterling of Hinds County, Mississippi, or William K. Easterling of Rankin County, Mississippi. Gabe Butler (MS). Born March 9, ca. 1854, in Amite County, Mississippi, son of Aaron and Letha Butler, slaves of William Butler. Marshal Butler (GA). Born December 25, 1849, son of John and Marilyn Butler. John was owned by Frank Collier and Marilyn by Ben Butler, both of Washington-Wilkes, Georgia. Ellen Butts (TX). Born near Centerville, Virginia. Mentions masters named William and Conrad, and a Dr. Fatchitt, who bought a birth-defective infant slave and pickled her in a jar. Dave L. Byrd (TX).

Land Allocation Efforts Stymied by the Johnson Administration

In the late stages of the Civil War and in its aftermath, the federal government (primarily Republicans) tried to relieve destitution among freedpeople and help them gain economic independence through attempts to allocate land. These efforts, both military and legislative, help explain why African Americans thought that compensation was attainable.

Special Field Orders No. 15, issued by Gen. William T. Sherman in January 1865, promised 40 acres of abandoned and confiscated land in South Carolina, Georgia, and northern Florida (largely the Sea Islands and coastal lands that had previously belonged to Confederates) to freedpeople. Sherman also decided to loan mules to former slaves who settled the land.

But these efforts were rolled back by President Andrew Johnson's Amnesty Proclamation of May 29, 1865. By the latter part of 1865, thousands of freedpeople were abruptly evicted from land that had been distributed to them through Special Field Orders No. 15. Circular No. 15 issued by the Freedmen's Bureau on September 12, 1865, coupled with Johnson's presidential pardons, provided for restoration of land to former owners. With the exception of a small number who had legal land titles, freedpeople were removed from the land as a result of President Johnson's restoration program.

Born August 10, 1846, five miles east of Livingston, Alabama. "My name was George Chapman, and I had five brothers: Anderson, Harrison, William, Henry and Sam; and three sisters: Phoebe, Frances and Amelia. My mother's name was Mary Ann Chapman and my father's name was Sam Young. Us all belonged to Governor Reuben Chapman of Alabama." Governor Chapman was born ca. 1800 in Caroline County, Virginia, and served as Alabama's thirteenth governor from 1847 to 1849. A Huntsville lawyer, he served in Congress from 1835 to 1847. Chapman tried to make peace between the Northern and Southern Democrats, but after Secession he served as an elector for Jefferson Davis. His house was burned during the war, and Chapman was imprisoned. He died in Huntsville in 1882. Freedmen`s Bureau Act had been established by Congress in March 1865 to help former slaves transition from slavery to freedom. Section four of the act authorized the bureau to rent no more than 40 acres of confiscated or abandoned land to freedpeople and loyal white refugees for a term of three years. At the end of the term, or at any point during the term, the male occupants renting the land had the option to purchase it and would then receive a title to the land.

But Johnson's restoration policy rendered section four null and void and seriously thwarted bureau officials' efforts to help the newly emancipated acquire land.

In June 1866 the Southern Homestead Act was enacted. It was designed to exclusively give freedpeople and white southern loyalists first choice of the remaining public lands from five southern states until January 1, 1867.

But homesteading was problematic on many different levels. The short period allotted by Congress (six months) worked against freedpeople because most were under contract to work or had leased land, through the bureau's contract labor policy, until the end of the year.

Certificate of membership in the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association. (Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG 15)

Congress also underestimated the time it would take for freedmen and loyal whites to successfully complete the process of securing a homestead. This process involved filing claims, waiting indefinitely until offices opened or reopened, and working to secure enough money to purchase land. Concurrently, freedpeople faced southern white opposition to settling land.

Moreover, Congress provided no tools, seed, rations, or any form of additional assistance to freedpeople, and most freedpeople's earnings just covered the bare necessities of life. Maintaining a homestead without assistance was almost impossible under those circumstances.

On March 11, 1867, House Speaker Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania introduced a bill (H.R. 29) that outlined a plan for confiscated land in the "confederate States of America." Section four of the proposed bill explicitly called for land to be distributed to former slaves:

Out of the lands thus seized and confiscated, the slaves who have been liberated by the operations of the war and the amendment of the Constitution or otherwise, who resided in said "confederate States" on the 4th day of March, A.D. 1861 or since, shall have distributed to them as follows namely: to each male person who is the head of a family, forty acres; to each adult male, whether the head of the family or not, forty acres; to each widow who is the head of a family, forty acres; to be held by them in fee simple, but to be inalienable for the next ten years after they become seized thereof. . . . At the end of ten years the absolute title to said homesteads shall be conveyed to said owners or to the heirs of such as are then dead.

Stevens knew that if federal land redistribution legislation failed to pass, freedpeople would be at the whim of former slaveholders for years to come. In support of his bill, he stated, "Withhold from them all their rights and leave them destitute of the means of earning a livelihood, [and they will become] the victims of the hatred or cupidity of the rebels whom they helped to conquer."

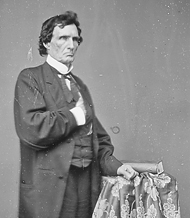

Senator Thaddeus Stevens, a powerful Radical Republican leader, was a staunch advocate foremancipation and championed civil and equal rights for blacks. (111-B-1458)

Republicans, during the 1868 campaign, even promised 40 acres and a mule to freedpeople. A couple of decades passed before any further concerted efforts were made to provide economic relief and security for ex-slaves, and when there was another major effort, it was not by the government but by former slaves and their allies.

Ex-Slave Pension Movement Begins as the Century Ends

By the last decade of the 19th century, the idea of trying to procure the enactment of pension legislation for ex-slaves for their years of unpaid labor was put into action.

The concept of ex-slave pensions was modeled after the Civil War–era program of military service pensions, and the first ex-slave pension bill (H.R. 11119) was introduced by Rep. William Connell of Nebraska in 1890.

It was introduced at the request of Walter R. Vaughan of Omaha, a white Democrat and ex-mayor of Council Bluffs, Iowa. He did not believe that it, or subsequent bills, should be identified as a pension bill but instead as "a Southern-tax relief bill." Vaughan recognized that pensions would financially benefit former slaves and would indeed be a semblance of justice for their years of forced labor. But the outcome he looked for involved ex-slaves spending their pensions in the South in order to give the devastated southern economy a financial boost.

The push for ex-slave pensions gained momentum in the 1890s and continued into the early 20th century. This grassroots movement was composed largely of former slaves, their family members, and friends. It emerged during the nadir of American race relations, roughly 1877 into the early 20th century.

Racial segregation officially became the law of the land with the U.S. Supreme Court's 1896 Plessey v. Ferguson decision, which upheld racial segregation under the "separate but equal" doctrine. Lynchings and race riots were at an all-time high, while civil rights and legal recourse for blacks were virtually nonexistent. Throughout the South, black men were disenfranchised and could not serve on juries.

James Lindsay Smith. "My birthplace was in Northern Neck, Northumberland County, Virginia. My mother's name was Rachel, and my father's was Charles," who were slaves of Thomas Langsdon. Smith, Autobiography of James L. Smith, pp. 116, 125-26. John Smith (AL). Born "somewhere in North Carolina." Sold to "Saddler" Smith of Selma, Alabama. Served "Saddler's" son, Confederate Jim Smith, in the Civil War. Lou Smith (OK). Her parents were Jackson Longacre of Mississippi and Caroline of South Carolina. Her father belonged to Uriah Longacre, her mother to a McWilliams family. Her mistress was Jo Arnold Longacre. Malindy Smith (MS).

The pension movement flourished in spite of, or even because of, these obstacles.

There were a number of ex-slave pension organizations within the movement—the National Ex-Slave Pension Club Association of the United States (Vaughan's Justice Party); the Ex-Slave Petitioners' Assembly; the Great National Ex-Slave Union: Congressional, Legislative and Pension Association of the U.S.A.; the Ex-Slave Pension Association; the Ex Slave Department Industrial Association of America; and others—but there is a paucity of documentation for groups other than the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association of the United States of America (MRB&PA). The ex-slave pension organizations did not work together collectively, but there is evidence that officers of at least a few of these organizations were interested in joining forces and consolidating their groups.

The MRB&PA was chartered on August 7, 1897, and had a dual mission: to petition Congress for the passage of legislation that would grant compensation to ex-slaves, particularly elderly ex-slaves, and to provide mutual aid and burial expenses.

Born ca. 1844 in Virginia, sold with his mother by Joe Poindexter and bought by Tom Murphy of (Pine Bluff?) Arkansas. Adam Singleton (MS). Born ca. 1850 near Newton, Alabama, slave of George Simmons. William Henry Singleton. Born August 10, 1835, at New Bern, North Carolina, the son of his master's brother. He claimed he was brought before Ambrose Burnside, but at the time of the expedition to capture Kinston (the town Singleton mentions as the goal of the Federal expedition), Foster was in command at New Bern, and Burnside was busy making a hash of things at Fredericksburg. Singleton, Recollections, pp. 8-9. Caroline Smith (AR). Born ca. 1855, slave of John F. Duncan, a farmer in Itawamba and later Pontotoc County, Mississippi. Charlie Tye Smith (GA). Born June 10, 1850, in Henry County, Georgia, near Locust Grove. Slave of Jim Smith. Classie Blackmond Smith (MS). Born ca. 1852, "belonging to the Blackmonds in Georgia." She mentioned a Miss Lucy, who could be twenty-one-year-old Lucy A. Blakeney, living in Smith County, Mississippi, in 1860 and born in Georgia. E. P. Smith in Fisk Expositor, Dedication of Jubilee Hall (FUA).

The association collected membership fees in order to help defray lobbying costs, printing/publication expenses, and travel expenses of the national officers. Monthly dues were reserved for mutual aid purposes (to aid the sick, the disabled, and for burial expenses). Ex-slaves and their allies gave their meager resources to help further the movement because they believed in the organization's mission. Dedication and charisma characterized the leaders of the association and enabled them to mobilize the masses.

By the late 1890s, the MRB&PA was the premiere ex-slave pension organization, claiming a membership in the hundreds of thousands. In addition to having a strong grassroots following, the MRB&PA was highly organized. The national officers established a charter, drafted a constitution and by-laws, held annual conventions, formed an executive board, started local chapters mostly in the South and Midwest, established enrollment fees and dues, advertised through circulars and broadsides, and advocated unity of purpose.

The organization supported a proposed pension payment scale based upon the age of beneficiaries that appeared in every ex-slave bill from 1899 onward. Ex-slaves 70 years and older at the time of disbursement were to receive an initial payment of $500 and $15 a month for the rest of their lives; those aged 60–69 years old would receive $300 and $12 a month; those aged 50–59 years old would receive $100 and $8 a month; and those under 50 would receive a $4 a month pension. If formerly enslaved persons were either very old or too ill to care for themselves, their caretakers were to be compensated.

Once a freedperson reached a certain age threshold, he or she would then be eligible for the higher pension. This proposed ex-slave pension payment scale is very similar to the Civil War pension gradation scale for soldiers with disabilities. Soldiers who became disabled as a result of military service received pension payments based on the nature of their partial disability and military rank. Over time, the Civil War pension program came to resemble a system of pensions for elderly veterans just as the ex-slave pension movement's main focus was to secure pensions to particularly aid the elderly.

Callie House, a widow, mother, and former slave, became a national leader of the ex-slave pension movement. (Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG 15)

The association's headquarters was in Nashville, Tennessee, where two of its most notable leaders, Isaiah H. Dickerson and Callie D. House, lived. Dickerson, an educator and minister, was the general manager and national promoter of the organization. House, a widow, laundress, mother of five, and former slave, was elected as the assistant secretary of the association in November 1898. She soon became a national promoter of the movement alongside Dickerson.

As the association's membership grew, government surveillance intensified. However, Dickerson, House, and other association officers were not aware of the federal government's intense interest in their organization and plans to undermine it and the larger movement.

Association Faces Strong Opposition to Pensions from U.S. Government

Three federal agencies—the Bureau of Pensions, the Post Office Department, and the Department of Justice—worked collectively in the late 1890s and into the early 20th century to investigate individuals and groups in the movement.

The officials who pursued the investigations thought the idea of pensioning ex-slaves was unrealistic because the government had no intention of compensating former slaves for their years of involuntary labor. Harrison Barrett, the acting assistant attorney general for the Post Office Department, admitted in an 1899 circular that "there has never been the remotest prospect that the bill would become a law."

In a February 7, 1902, letter to the commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, the commissioner of pensions blamed the ex-slave pension organizations for arousing false hopes for "reparation for historical wrongs, to be followed by inevitable disappointment, and probably distrust of the dominant race and of the Government."

Special examiners of the Law Division of the Bureau of Pensions attended slave pension association meetings, took depositions from officers (national and local), and sent letters to officers and members to determine if officers were representing themselves as officials appointed by the United States Government.

The Bureau of Pensions also sent circulars to agents affiliated with various ex-slave pension organizations. Although these circular usually carried the disclaimer, "While any class of citizens has an unquestioned right to associate for the purpose of attempting to secure legislation believed to be advantageous," these words were often simply a formality. The bureau's inspectors did not find evidence to incriminate any of the influential MRB&PA officers whom they suspected of fraud.

The Post Office Department took action when it presumed that the U.S. mails were being used to defraud ex-slaves. The Post Office used its extensive antifraud powers against the movement, issuing fraud orders to organizations and officers.

On September 20, 1899, Barrett issued a fraud order against the MRB&PA and its national officers (Dickerson, Rev. D. D. McNairy, Rev. N. Smith, Rev. H. Head, and House), forbidding the delivery of all mail matter and the payment of money orders.

Once the mail was intercepted, it was either returned to senders marked "Fraudulent" or simply withheld from the intended recipients. The fraud order and obstruction of mail proceeded even though the Post Office had no concrete evidence that the association had acted illegally.

In letters to both Barrett and Nashville Postmaster A. W. Wills, Dickerson, House and other officers invoked their first amendment rights (namely their right to assemble and right to petition the government), 14th and 15th amendment rights (citizenship rights and voting rights), and highlighted the dire condition of old ex-slaves.

In both correspondence and depositions, national and state officers of the MRB&PA also repeatedly denied the accusation that the movement was fraudulent or a lottery. They even hired an attorney to represent them and try to get the fraud order revoked. These efforts were futile. The Post Office Department was determined to maintain the fraud order set in motion in 1899 against the association and its founding officers and was continually searching for ways to limit their influence.

The Department of Justice gathered information to probe the activities of the officers, especially House, not to counteract any fraudulent beliefs. The MRB&PA provided the department with a list of local agents in order to show that they were not a sham organization, but the government disregarded this proof.

There were individuals who, under the guise of supporting the movement, took advantage of ex-slaves. They were either affiliated with an ex-slave organization or pretended to be affiliated with the movement to swindle money. To counter any misuse of funds within their organization, the MRB&PA had a grievance committee that would determine if an officer was guilty of squandering funds, and it took necessary action against him or her.

The goal of the investigations by the Bureau of Pensions, Post Office Department, and Justice Department was not to determine whether former slaves had a legitimate grievance or claim, but to stifle the movement.

John Smith (AL). Born "somewhere in North Carolina." Sold to "Saddler" Smith of Selma, Alabama. Served "Saddler's" son, Confederate Jim Smith, in the Civil War. Lou Smith (OK). Her parents were Jackson Longacre of Mississippi and Caroline of South Carolina. Her father belonged to Uriah Longacre, her mother to a McWilliams family. Her mistress was Jo Arnold Longacre. Malindy Smith (MS). Born ca. 1860 in old Choctaw (now in Webster) County, Mississippi, daughter of Henry Att and Harriet Edwards. Melvin Smith (GA). Born 1841 in Beaufort, South Carolina, son of Henry and Nancy Smith, slave of Jim and Mary Farrell. Nancy Smith (GA). Born ca. 1858, daughter of Jack and Julia Carlton, slave of Joe Carlton of Athens, Georgia. Nellie Smith (GA). Born in 1856 in Harnett County, North Carolina, daughter of Atlas and Rosetta Williams, slave of Jack Williams. Paul Smith (GA). Born the slave of Jack Ellis of Oglethorpe County, Georgia. Samuel Smith (TX).

The pension bills submitted to Congress received little serious attention. The Senate Committee on Pensions examined S. 1176 (a bill essentially similar in language to all of the other bills) and wrote an adverse report. This committee received its information (and thus a tainted view of the movement) from none other than the Post Office Department and the commissioner of pensions. The report described freedpeople in the movement as "ignorant and credulous freedmen," and the committee concluded that "this measure is not deserving of serious consideration by Congress" and recommended "its indefinite postponement."

Senate Bill 1176 is representative of the ex-slave pension bills introduced in both houses of Congress. This bill's new feature was the proposed pension payment scale based upon the age of beneficiaries. (Records of the U.S. Senate, RG 46)

When House learned of the committee's report, she drafted a letter to the commissioner of pensions refuting its allegations and explaining the objectives of the association. She invoked both the Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution. Because one of the main objectives of the association was petitioning Congress for pensions to aid old ex-slaves, House reminded the commissioner that "the Constitution of the United States grants it[s] citizens[s] the priviledge [sic] to petition Congress for a redress of Greviance[s] [sic] therefore I cant see where we have violated any law whatever."

In 1901 Dickerson was found guilty of "swindling" in city court in Atlanta, Georgia. The press reported that he would have to pay a $1,000 fine or be sentenced to one year on the chain gang. The conviction was overturned later that year by the Georgia State Supreme Court, which reasoned that in order to be convicted of swindling, Dickerson would have had to have claimed that an ex-slave pension bill had passed and become law or that an appropriation had been made to pay pensions, and not simply that he was advocating for the passage of pension legislation.

Then in May 1902 a special examiner of the Bureau of Pensions conducted an inquiry into Dickerson and drafted an affidavit of the investigation but found nothing incriminating. When Dickerson died in 1909, House soon became the leader in the forefront of not only the MRB&PA but of the movement.

After Congress responded so unfavorably to the pension movement, House took the issue to the courts.

Hattie Sugg (MS). "Born up Big Creek on the old Armstrong place here in Calhoun county [Mississippi]." Eliza Suggs. Her parents "were slaves. Father was born in North Carolina, August 15, 1831. He was a twin, and was sold away from his parents and twin brother, Harry, at the age of three years." His father's parents "named him James. So at this time his name was James Martin. He was sold by Mr. Martin for a hundred dollars, and taken to Mississippi. Afterward he was sold to Jack Kendrick, and again to Mr. Suggs, with whom he remained until the war broke out." Born after the war with dwarfism, unable to walk, Suggs lived in Nebraska, where she became an active evangelist. Suggs, Shadows and Sunshine, pp. 44-47. ___ Sutton in Egypt, ed., Unwritten History of Slavery, p. 34.

In 1915 the association filed a class action lawsuit in federal court for a little over $68 million against the U.S. Treasury. The lawsuit claimed that this sum, collected between 1862 and 1868 as a tax on cotton, was due the appellants because the cotton had been produced by them and their ancestors as a result of their "involuntary servitude."

The Johnson v. McAdoo cotton tax lawsuit is the first documented African American reparations litigation in the United States on the federal level. Predictably, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia denied their claim based on governmental immunity, and the U.S. Supreme Court, on appeal, sided with the lower court decision.

Maria Tilden Thompson (TX). Tim Thornton (GA). Born ca. 1836, the slave of Mrs. Lavinia Tinsley, whose plantation was not far from Cascade, near Danville, Virginia. Jim Threat (OK). Born ca. 1851. "I was one of twenty-two children. All of us lived to be grown except Tommy, Ivory and a little girl." His brother Bill Threat was a preacher in Parsons, Kansas. His mother, her brother, his grandmother, and his aunt belonged to an Indian named Johnnie Bowman. "He got in a tight fix and sold them to Russell Allen, and he made him promise not to sell them one by one but in pairs or all together. Russell sold his grandmother and aunt to Hollis Montgomery." Lucy Thurston (MS). Lived in Flemingsburg, Kentucky, slave of Claiborne Woods. J. T. Tims (AR). Born September 11, 1853, in Jefferson County, Mississippi, six miles east of Fayette. Son of Daniel and Ann Tims of Lexington, Kentucky. Slave of Blount Steward. When Daniel protested Steward's beating his wife, Steward struck him with a hammer. Daniel threatened him, then ran off with his family, up the river to Natchez. "We went there walking and wading." Alonza Fantroy Toombs (AL).

The Post Office Department was unrelenting as it continued to search for means to limit House's influence and curtail the movement. After a prolonged investigation, House was arrested and indicted on charges of mail fraud. She was accused of sending misleading circulars through the mail, guaranteeing pensions to association members, and profiting from the movement. She denied ever assuring members that the government would grant pensions or that a law had been passed providing pensions for ex-slaves. There was also no evidence that she profited from the movement.

William Henry Towns (AL). Born December 7, 1864, in Tuscumbia, Alabama, son of Jane Smoots of Baltimore and Joe Towns of Huntsville, Alabama. Emmeline Trott (MS). Born in North Carolina. As a toddler she was taken by the Thompson family to Pontotoc, Mississippi. When she was six her mistress died, willing her to a son, Turner Thompson. Her mother was sold, loaned to Mrs. Josie Pinson Wilcox, and then bought by Captain and Mrs. Sara Trott, whose slave, Alfred Trott, she married. William B. Trotter. Sydnor, Slavery in Mississippi, p. 137. Harriet Tubman. Born Araminta Ross ca. 1820 in Dorchester County, Maryland, she married a free black named John Tubman and adopted her mother Harriet's first name. Afraid she was about to be sold, she escaped in 1849 by following the North Star into Pennsylvania. In Philadelphia she earned enough money to return to the South, once to spirit her sister to freedom, again to rescue her brother, and a third time to fetch her husband. By then he had remarried, however, which proved fortunate for the many slaves—estimates range from 70 to 300—she would rescue, for which Southerners put a $40,000 bounty on her head. By the beginning of the war she had run nineteen missions. She died in Auburn, New York, in 1913.

The Post Office identified activities as mail fraud without definitive evidence, and their decisions to deny use of the mails were nearly impossible to appeal.

After a three-day trial in September 1917, an all-white male jury convicted her of mail fraud charges, and she was sentenced to a year in jail at the Missouri State Prison in Jefferson City. She was released from prison in August 1918, having served the majority of her sentence, with the last month commuted.

This movement, against insurmountable odds, pressed for the passage of pension legislation to no avail. But being labeled as fraudulent—especially by determined federal agencies—sealed its fate.

Miranda Booker Perry is an archivist trainee in the Textual Archives Division at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. She has worked on a number of military records projects and has delivered presentations on the ex-slave pension movement. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate in history at Howard University.

Rhodus Walton (GA). Born ca. 1852, son of Antony and Patience Walton of Lumpkin, Stewart County, Georgia. When he was three weeks old, his mother, along with the three younger children, was sold to a wealthy planter named Sam B. Walton. George Ward (MS). Born on the Ledbetter plantation, three miles west of Tupelo, Mississippi, son of a Negro mother and a Chickasaw father. His mother was stolen from Winchester, Tennessee, and taken to the Cotton Belt. "She was sold six times, because no man could whip her. Her name was Amy Givhan [Gibbon?]. Her first two children were girls; the oldest one, Susan, lived to be 96. My step-father helped to build Martha Washington School and Chickasaw College at Pontotoc. I was a slave of the late Dr. Edward Givhan's father, ten miles south of Pontotoc." Sam Ward in Mellon, ed., Bullwhip Days, p. 343.

Note on Sources

Records on the ex-slave pension movement housed at the National Archives reveal an immense amount about a social movement on the periphery of history, the organization at the epicenter of the movement, and the government's response to it.

Dave Weathersby (MS). Born 1851 near Monticello, Lawrence County, Mississippi, slave of William Weathersby. Jennie Webb (MS). Born 1846, one of twenty-six slaves of Fredman H. C. Dent of Rankin County, Mississippi. William Webb. Born 1836 in Georgia, moved with his master to Italia in central Mississippi. After escaping from his master, he became a major figure in the Underground Railroad. Webb, History, pp. 13-16, 30, 33, 36. John Wells (AR). Slave from Edmondson, Arkansas, refugeed to Texas. James West (TX). Born ca. 1853, one of six slaves of William West in Tippah County, near Ripley, Mississippi. Maggie Wesmoland (Westmoreland?) (AR). Born ca. 1858 (according to slave schedule for 1860), the daughter of Simon and Caroline Wright, slaves of Benjamin P. (or S.) and June C. Cuney of Sicily Island, Catahoula Parish, Louisiana. Eliza White (AL). Born in Alabama. Julia White (AR). Born ca. 1857. Daughter of James Page Jackson, who was born on the Jackson plantation in Lancaster County, Virginia. "A man named Galloway bought my father and brought him to Little Rock, Arkansas. There were fourteen of us, but only ten lived to grow up." Mingo White (AL). Born in Chester, South Carolina, raised in Alabama. "When I was about four or five years old, I was loaded in a wagon with a lot more people in it" and sold. "Whatever become of my mammy and pappy I don't know for a long time." During the auction, "us had to tell them all sorts of lies for our Master or else take a beating."

National Archives Microfilm Publication M2110 reproduces the series Correspondence and Case Files Pertaining to the Ex-Slave Pension Movement, Law Division, Bureau of Pensions, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group (RG) 15. These records include correspondence, circulars, broadsides, petitions to Congress, depositions, pension bills, certificates of membership, affidavits, and memorandums. The numerous letters from ex-slaves and their descendants inquire about the status of ex-slave pension legislation, provide information on their former slave status, and urge the government to pay pensions. Certificates mailed to the bureau involvement in and support of the ex-slave pension movement. There are also letters between Post Office officials and pension officials.

Williams (OK). Born July 18, 1857, in Jefferson County, Arkansas. Daughter of a white overseer named Kelly and Emmaline, a slave of a family named Burns. Hulda was the wife of a Bond slave, George Washington Bond. Isaac D. Williams. Born ca. 1821 in King George County, Virginia, slave of John O. Washington. Williams, Sunshine and Shadows, p. 89. Mollie Williams (MS). Born September 15, 1853, about three miles from Utica, Mississippi, slave of George Newsome. "Pappy was name Martin Newsome," and "Mammy was a Missourian name Marylin Napier Davenport. She was big and strengthy," and Newsome "wanted her powerful bad," so his wealthy uncle, John Davenport, bought her and loaned her to him, on condition that each receive every other child she bore. Olin Williams (GA). Born around 1854, slave of John Whitlow of Clarke County, Georgia. William Ball "Soldier" Williams III (AR). Born in Greensburg, Arkansas. Not listed under this name in Union Army rolls. In his quote regarding black troops being employed as shields, I have changed "they" to "us" for clarity's sake.

Fraud Order Case Files, part of the Records of the Post Office Department, RG 28, include correspondence, fraud orders, memorandums, newspaper clippings, and copies of constitution and bylaws. Special Field Orders, No. 15, Headquarters Military Division of the Mississippi, January 16, 1865, is found in Orders & Circulars, ser. 44, Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's–1917, RG 94.

Other NARA records that contain material pertaining to the movement include the General Records of the Department of Justice, RG 60; Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21; Records of the U.S. Senate, RG 46; and Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, RG 233.

The remar

Sarah Wilson (OK). "I was born in 1850 along the Arkansas river, about halfway between Fort Smith and old Fort Coffee and the Skullyville boat landing on the river. The farm place was on the north side of the river on the old wagon road what run from Fort Smith out to Fort Gibson. I was a Cherokee slave, and now I am a Cherokee freedwoman; and besides that, I am a quarter Cherokee my own self." Temple Wilson (MS). Born ca. 1857, slave of Jim Percow in Madison County, Mississippi. Willis Winn (TX). Claimed to have been born ca. 1832 when interviewed in 1938. Owned by Bob Winn of Louisiana. Rube Witt (TX). Born ca. 1850, slave of Jess Witt of Texas. George Womble (GA). His master was Robert Ridley of Clinton, Georgia. Anna Woods (AR). Lived near Natchez, Mississippi. Samuel M. Woods in Jordan, Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees, p. 128. ks by Thaddeus Stevens in support of H.R. 29 are in the Congressional Globe, 40th Cong., 1st sess., March 19, 1867, pp. 203, 205. Walter R. Vaughan's pamphlet, Vaughan's "Freedmen's Pension Bill": A Plea for American Freedmen is housed at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University. Walter Fleming's, "Ex-Slave Pension Frauds," University Bulletin Louisiana State University Vol. I-N.S., No. 9 (September 1910): 6 was first published in the South Atlantic Quarterly, April 1910. The "cotton tax" case, Johnson v. McAdoo, was decided on November 14, 1916, by the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia (45 App. D.C. 440); the Supreme Court sustained that decision in 244 U.S. 643 (1917).

Born July 4, 1855, at Pittsboro, Calhoun County, Mississippi. "My papa was Nelson Woodward who was born in Richmond, Virginia, and my mama was Dolly Pruitt from Alabama. My brothers was Jeff, Sam, Ben, and Jim and my sisters was Tilla, Lena and Rosetta. My job during the war was to lead [blind] Bob Conner all through the war. You know, Master Conner was the papa of Mr. Fox Conner who is now such a big man in the army." Sam Word (AR). Born February 14, 1859, in Arkansas County, the slave of Bill Word. Ellaine Wright (TX). Born March 1, 1840, just outside Springfield, Missouri; slave of Tom Evanson. Married Pete Wright in 1866. Henry Wright (GA). Born the slave of a family named House. His master "was not present, for when he heard of the approach of Sherman he took his family, a few valuables and some slaves and fled to Augusta." John Wright in Armstrong, Old Massa's People, pp. 276-77.

The ex-slave pension movement was relatively unknown until historian Mary Frances Berry rescued it from obscurity in her essay "Reparations from Freedmen: 1890–1919: Fraudulent Practices or Justice Deferred?" Journal of Negro History 57 (July 1972): 219–230, and in her book My Face Is Black Is True: Callie House and the Struggle for Ex-Slave Reparations (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005).

Litt Young (TX). Slave of a Dr. Gibbs in Vicksburg, Mississippi, and refugeed to Texas after Vicksburg's surrender. Robert Young (MS). Born May 15, 1844, about twelve miles east of Crystal Springs, Mississippi. Son of Emily Watkins and Prince Watkins, slave of Gus Watkins and Margaret Watkins and their son Henry, who disemboweled his own father during a fight over a slave. "After that Miss Margaret married Freeman Young and that's how come we come by name of Young."

Also consulted were Claude F. Oubre, Forty Acres and a Mule: The Freedmen's Bureau and Black Land Ownership (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978); John Hope Franklin, Reconstruction: After the Civil War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961); Carter G. Woodson, The Mis-Education of the Negro (Washington, DC: The Associated Publishers, Inc., 1933); and Michael T. Martin and Marilyn Yaquinto, eds. Redress for Historical Injustices in the United States: On Reparations for Slavery, Jim Crow, and Their Legacies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007

|

No comments:

Post a Comment